“Everyone keeps at a distance.”

(David Hume, A Treatise of Human Nature, 1739-40, Conclusion to Book 1)

Is someone up above running a global version of Mary Ainsworth’s “Strange Situation” procedure?

Ainsworth, a pioneering attachment theorist, devised the Strange Situation to examine how very young children responded to being separated from their mother. Her study recorded the responses of a group of one-year-olds and identified three distinct behavior patterns: Group A exhibited what Ainsworth characterized as “avoidant” behavior, Group B exhibited what Ainsworth termed “secure” behavior, and Group C exhibited what Ainsworth termed “resistant” or “ambivalent” attachment.

The kind of behaviors understood as constitutive of avoidant attachment are as follows:

“increasing distance between self and the person, whether through locomotion or by leaning away from; turning the back on the person; turning the head away; averting the gaze; avoidance of meeting the person’s eyes; hiding the face; or simply ignoring the person.”

The strange situation we currently occupy is one in which Group A behavior is suddenly mandatory.

Describing a follow-up study to the Strange Situation, Ainsworth observes how each group of children responded to a situation in which their mother was asked to sit at a distance from them:

“Group-B children spent more time within 6 feet of the mother than the A children, under all conditions. When mother was on the sofa, C children spent more time within 6 feet of her than did B children. It may be noted that the sofa was in the living-room area, out of sight of a child in the play area. Presumably the C children interpreted the mother’s move to this more distant position as indicating a decrease in her accessibility, whereas the B children considered her still accessible.”

Group A (avoidant) types, then, are practiced at keeping themselves more than six feet from others. Do you now find yourself pre-emptively stepping out into a street so you don’t have to cross the path of someone walking the other way? In normal times, this pre-emptive avoidance of another person would seem like a classic Group A move: as Ainsworth explains, avoidant behavior “protects the baby from reexperiencing the rebuff that he has come to expect.” The avoidant person, in other words, rebuffs you as a defense mechanism, before you can rebuff them.

But in our new strange situation, this kind of avoidant behavior feels, increasingly, like a basic courtesy. It almost feels aggressive to stay on the sidewalk when you’re within twenty feet or so of another person walking towards you.

I’m not a mental health professional, and I’m not going to diagnose myself; but let’s just say that, ever since I started reading a lot of attachment theory a couple of years ago, I’ve felt a strong affinity with Group C. Group C are the resistantly or ambivalently attached children. Remember the example above in which the Group C children spend more time with their mother than the secure children once their mother is in the other room?

Classic Group C.

We Group C types are not especially interested in you when you’re in the room with us, but if you leave? That’s when you suddenly become very interesting to us.

Group C behavior might seem perverse; but I think of it, more indulgently, as an especially heightened manifestation of the dynamic at play in all attachment behavior: the effort to maintain a “set-goal” of proximity to the attachment figure that the child finds reassuring.

Here is John Bowlby, for example, describing normal attachment behavior in ways that make Group C behavior just seem, well, sensible:

“When a mother rebuffs her child for wishing to be near her or to sit on her knee it not infrequently has an effect exactly the opposite of what is intended—he becomes more clinging than ever. Similarly, when a child suspects his mother is about to leave him behind, he insists remorselessly on remaining by her side. When, on the other hand, a child observes that his mother is attending to him and is ready to respond whenever he may desire greater proximity to her, he is likely to be content and may explore some distance away. Although such behaviour may appear perverse, it is in fact what is to be expected on the hypothesis that attachment behaviour fulfills a protective function. Whenever mother seems unlikely to play her part in maintaining proximity a child is alerted and by his own behaviour ensures that proximity is maintained. When, on the other hand, mother shows herself ready to maintain proximity her child can relax his own efforts.”

Here, then, is my hypothesis for why, even aside from the anxiety about illness and suffering that the pandemic is causing, this situation triggers everyone’s attachment issues in ways that are particularly intense and chronic:

- This is a disaster, and disasters trigger attachment behavior. “When,” Ainsworth writes, “the attachment system is activated at a high level of intensity—for example, by severe illness or disaster—the person seeks literal closeness to an attachment figure.”

- However, the nature of this particular disaster is such that the prescription for mitigating it—social distancing—entails withholding the most important source of comfort for a person in severe distress: literal closeness to loved ones.

- So then, in addition to the disaster that is activating our attachment behavior, the treatment for the disaster—social distancing—itself constitutes a secondary cause that further activates attachment behavior. In other words, the very fact that physical contact is being withheld from us makes us long for it even more.

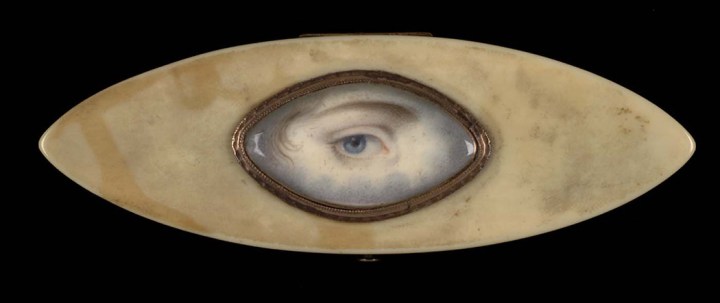

Now, obviously, this isn’t as disastrous for us, as adults, as it would be for an infant, because adults can readily express and receive attachment via alternative, ugh, modalities. Ainsworth observes, “the older child or adult may employ distant modes of interaction to reaffirm the accessibility and responsiveness of the attachment figure. Telephone calls, letters, or tapes may help to ameliorate absence; photographs and keepsakes help to bolster the symbolic representation of the absent figure.”

(Note to any younger readers: the modes of communication to which Ainsworth refers here are what you can think of as protozooms.)

However, as Ainsworth warns, “representations cannot entirely supplant literal proximity and contact … even an older child or adult will sometimes want to be in close bodily contact with a loved one, and certainly this will be the case when attachment behavior is intensely activated—say, by disaster, intense anxiety, or severe illness.”

I realize that I am just stating the obvious here, but it feels important to say because it helps pinpoint what is so distinct about this global disaster: remoteness is not only the prophylactic for but also (for the lucky ones) the constitutive experience of the disaster.

In my own case, the pains caused thus far by this remoteness—loneliness, anxiety, listlessness, etc.—have been relatively mild. I’d say they fall into the category, paraphrasing David Hume, of pleasures languishing when enjoyed apart from company. What is scarier is the prospect of future pains, pains that, as Hume observes, “becomes more cruel and intolerable” in isolation. A few months ago, when my Mum was visiting and had a bad fall, I could literally put my arms around her to help lift her to her feet. Knowing that I would not be able to put my arms around her or any other loved ones who fell ill with this virus is the intolerable prospect.

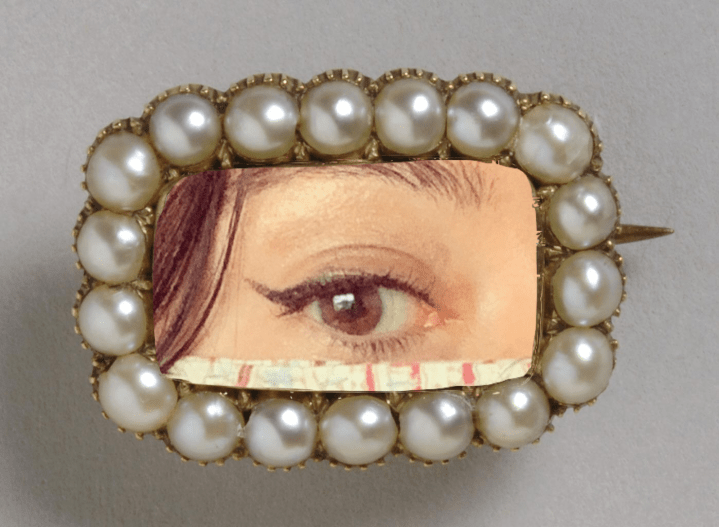

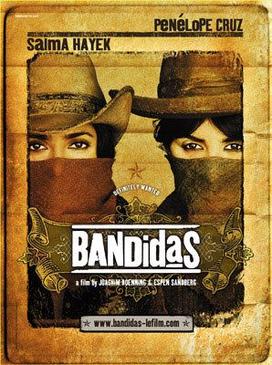

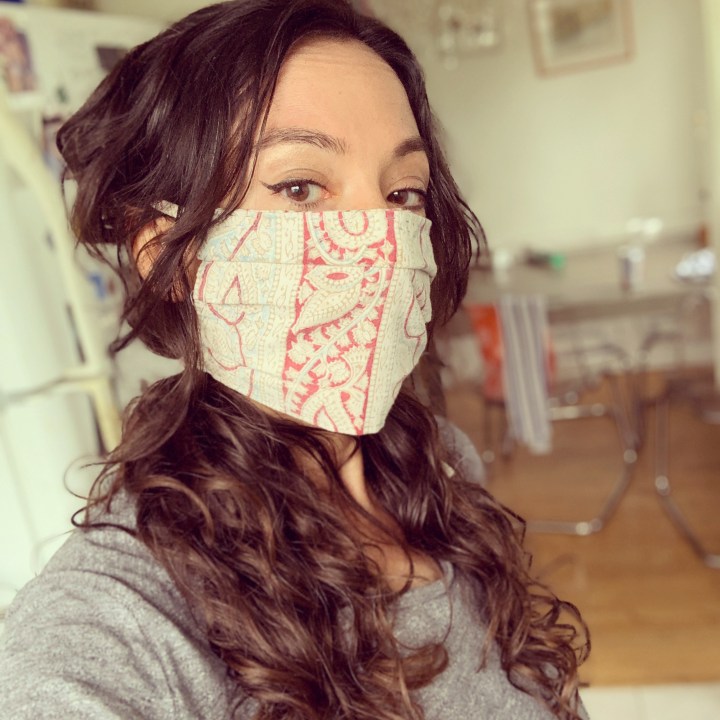

Maybe it’s time to start making eyes again.

Maybe it’s time to start making eyes again.